Letter of Attorney (Poder)

What did a letter of attorney look like, what were its component parts, who were the actors involved in their production, and what did they authorize legal agents to do?

Notarial templates. As was the case for all Spanish American notarial records, there were templates and formulas for different notarial genres, which could be found in notarial manuals that circulated widely in the Spanish Empire.[1]

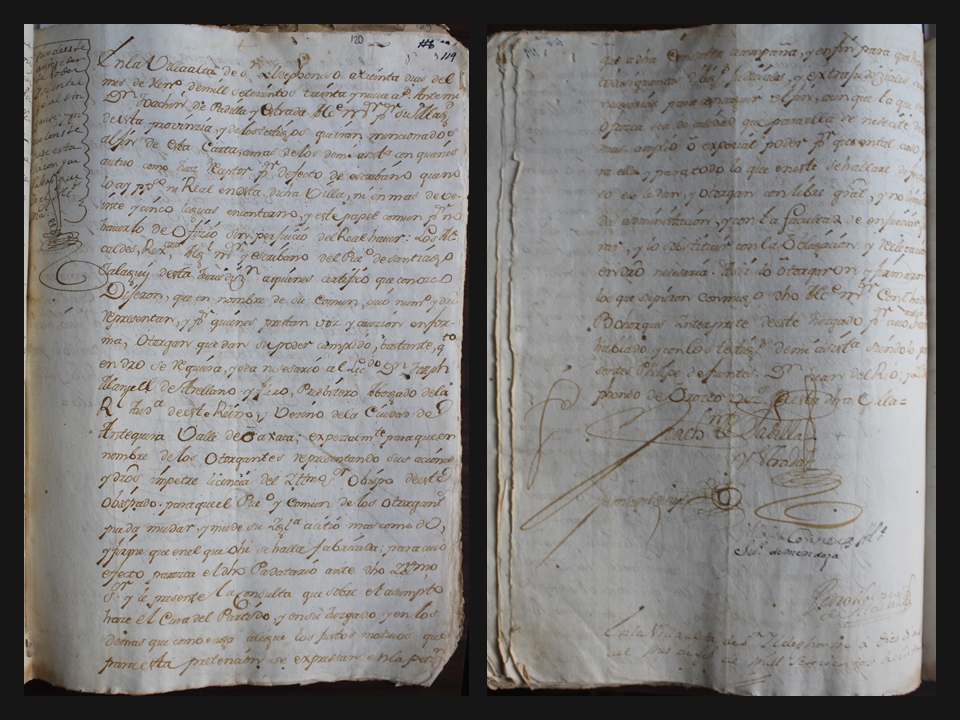

Opening Formula. The opening formula of a letter of attorney began with the place, date and the name of the presiding notary, Spanish magistrate (alcalde mayor and after 1790, subdelegado), or lieutenant magistrate (teniente). In the case of Villa Alta, there was no notary. According to the calculus of colonial officials who were short on funds with which to pay provincial bureaucrats, the district of Villa Alta was too remote, and its majority indigenous population too “rustic,” to justify the constant presence of a notary in the district seat. In lieu of a notary, the Spanish magistrate or lieutenant, and two witnesses (testigos de asistencia), who were local notables and had some legal knowledge, authorized and signed letters of attorney. The notary’s absence is noted in the opening formula.

Grantors. Next appears the name(s) of the grantor(s), and if the grantor(s) were Indian(s), his social status, town(s) or village(s) of origin, and if they were municipal authorities, the offices that each of them held. If the grantors were the municipal authorities of their town(s), it was noted that they granted power of attorney on behalf of their municipality or municipalities.

Interpreter. In letters of attorney in which Indians were grantors, the presence of an interpreter was acknowledged, and his name recorded. Often, letters of attorney stated that although some or all of the grantors were speakers of Castilian Spanish, they communicated through an interpreter. According to notarial manuals, an interpreter’s presence was required for legal and notarial business involving Indians, even if they spoke Spanish and did not require an interpreter to communicate. In short, the Interpreter’s presence guaranteed the legitimacy of the proceedings. It was through the interpreter’s voice that power of attorney was granted. In Villa Alta, a multilingual district, it was not unusual for more than one interpreter to attend notarial and legal proceedings; each interpreter translated in a different language (generally, a variant of Zapotec or Mixe).

Grantee or Legal Agent (apoderado). The name of the person who was granted power of attorney appears next, as well as important information about their social and professional status, and town or city of residence, which usually corresponded with the location of a court (i.e. the district court of Villa Alta, ecclesiastical court of Antequera (Oaxaca), the supreme court (Real Audiencia) of Mexico City, or the royal court in Madrid. If the apoderado was an indigenous man from an Indian town in Villa Alta, he tended to be from the parish seat.

Power of Representation. There were two types of letters of attorney, one for specific legal business or litigation (poder especial), and the other for all legal business (poder general).

In the case of a poder general, there is a formula that grants the legal agent representative power in civil and criminal cases, in ecclesiastical and civil courts, and even the power to appear in front of the highest imperial authority: the King of Spain. In the case of a poder especial, the legal agent is empowered to pursue specified legal business. In this example of a poder especial, the municipal authorities of the town of Santiago Yalahui authorize their legal agent to request a license from the Bishop of Oaxaca to move their church to a new location.

Letters of attorney empowered the legal agent to be a handler of information. He could request copies of testimony, legal documentation, and notarial records pertaining to the grantor’s legal business from any court where it might be archived. He could swear or take oaths on behalf of the grantors, recuse them from a case or dispute, appeal a judge’s unfavorable ruling, and pursue any necessary legal measures to see a case to its conclusion.

Terms. The terms of the power of attorney relationship are spelled out in the letter of attorney: with their signature(s), the grantor(s) pledged their personal worth (sus personas) and that of their communities (bienes de sus comunes) to secure the representation of the grantee, for which they had to pay. Their signatures also authorized Spanish officials to hold them legally accountable for payment. In this regard, power of attorney did not fall under the umbrella of the Spanish law that guaranteed Indians as legal minors access to free legal counsel by a salaried court-appointed lawyer (procurador de indios). Power of attorney required the marshaling and transfer of communal resources from native towns to licensed and unlicensed legal professionals.

Signatures. The letter of attorney ends with the signatures of the grantors who knew how to sign, the interpreter, the magistrate or his lieutenant, and the two court witnesses.